Behind Chinestory: Designing a Smarter Way to Learn Chinese

Dr. Haiyan Fan is a published author, TEDx speaker, and creator of Chinestory: Learning Chinese through Pictures and Stories, a pedagogical innovation designed to help curious minds learn the Chinese language through beautiful illustrations and the origin stories behind each character’s creation.

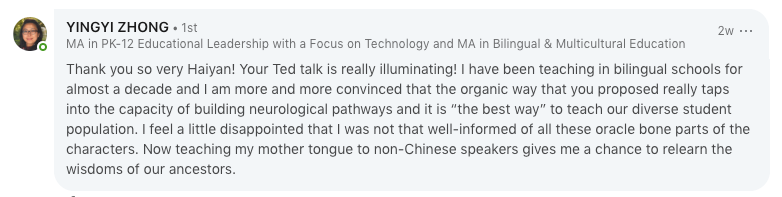

With formal training in Applied Linguistics, UX Design and Artificial Intelligence, Dr. Fan developed a unique approach to mastering this pictograph language. In her TEDx talk, “Learn Chinese in the 21st Century”, she outlined the method of growing a “Chinese language tree” by first learning the “seed” radical and then unlocking 10x more characters that share the same etymological origin.

Her innovative work earned the prestigious 2019 International IF Design Award in the education category. Since moving to Northwest Arkansas three years ago, Dr. Fan has coached students in Mandarin Chinese, leading them to achieve 1st Place in the U.S. National Chinese Speech Contest consecutively in 2023 and 2024. Recognized for her contributions to Chinese education, she was also awarded the 2024 U.S. Heartland China Association Teacher Award. Dr. Fan obtained her dual Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics & Management Information Systems at the University of Arizona, where she worked as a research assistant at the Artificial Intelligence Lab, and Ph.D. degree at Texas A&M University.

📖 Want to know the full Dr.Fan's backstory on this innovator's journey?

Read Dr. Fan’s journey on Medium →

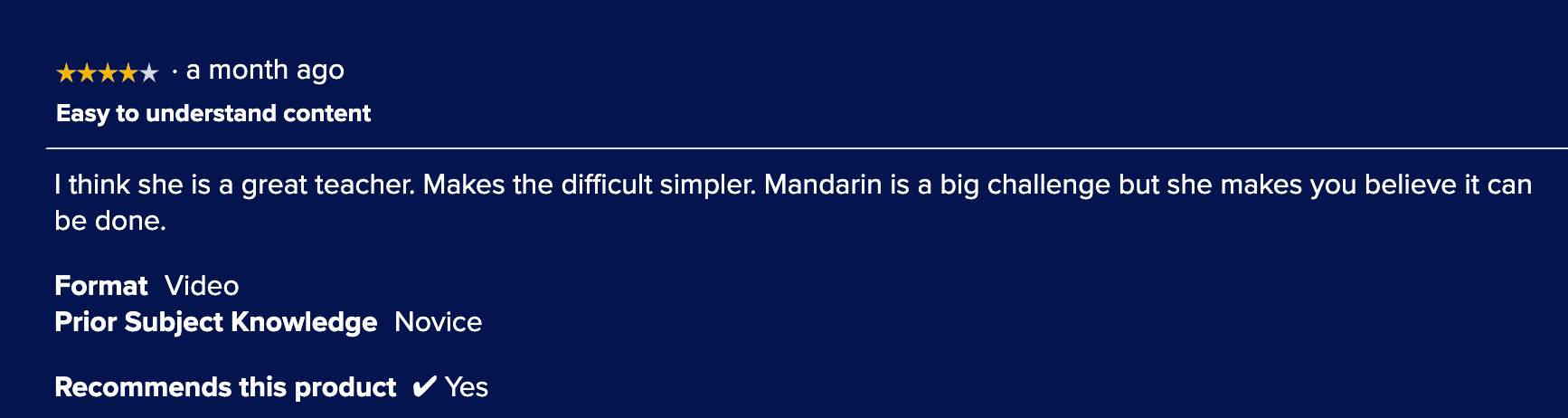

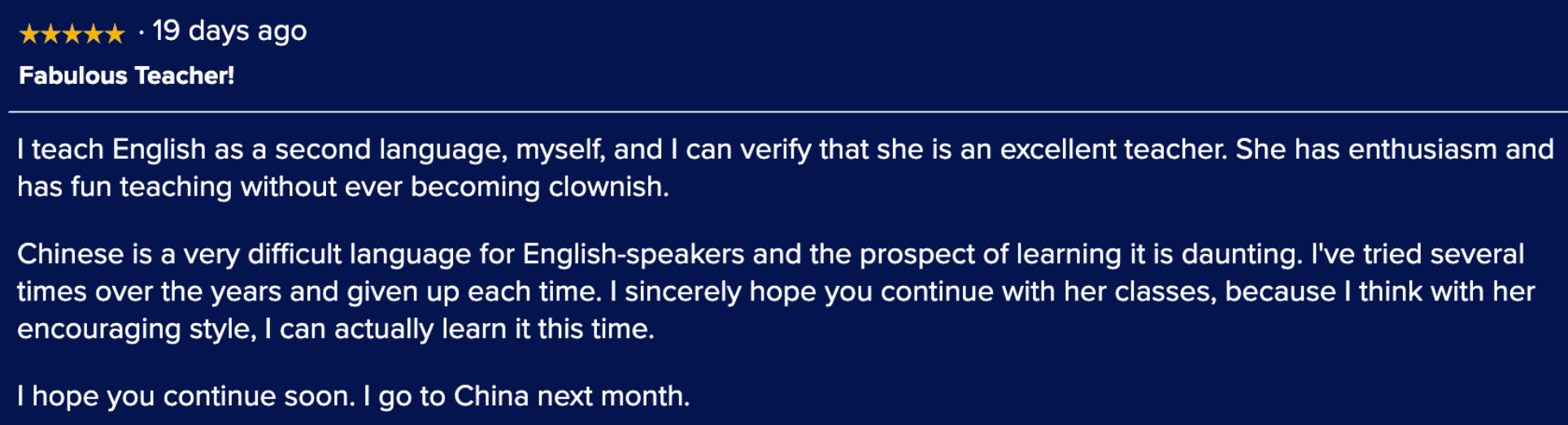

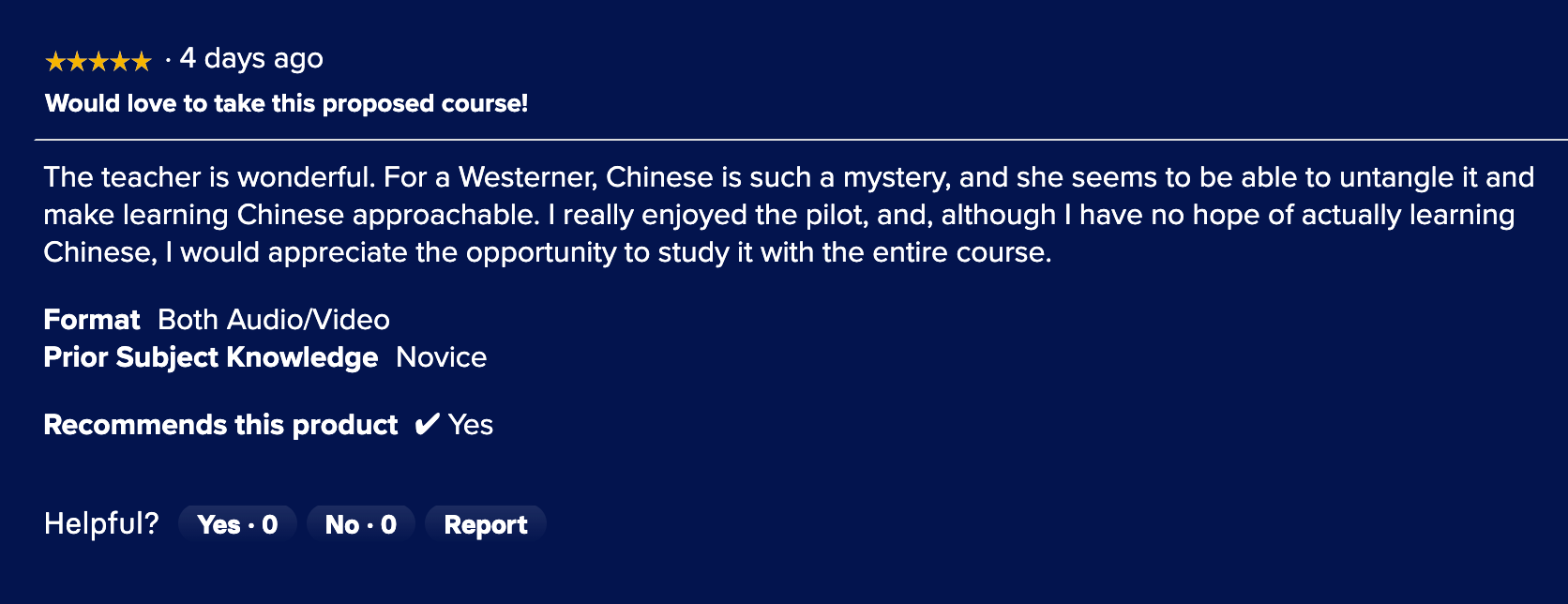

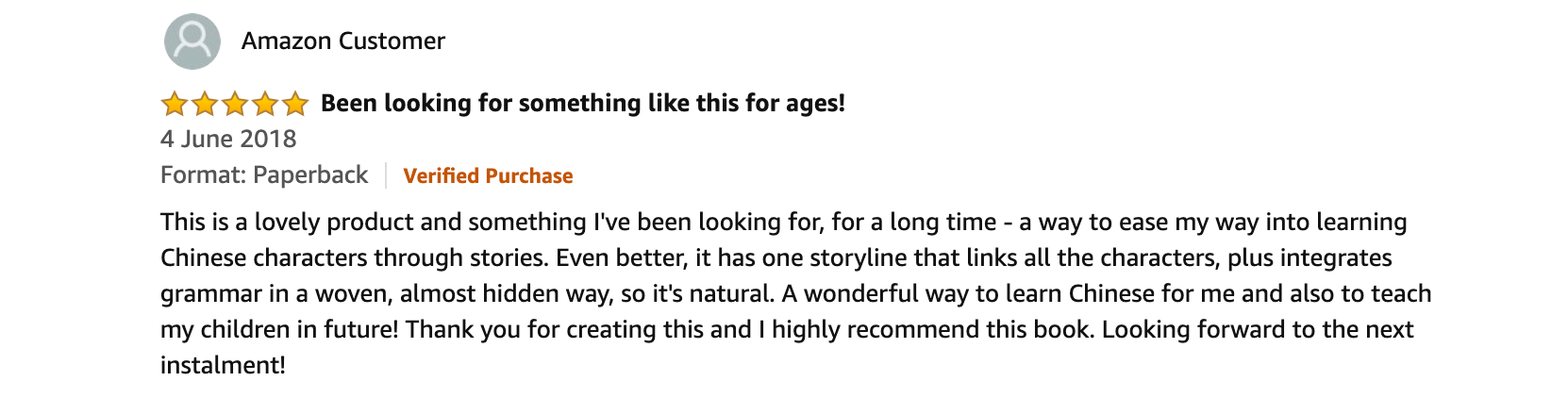

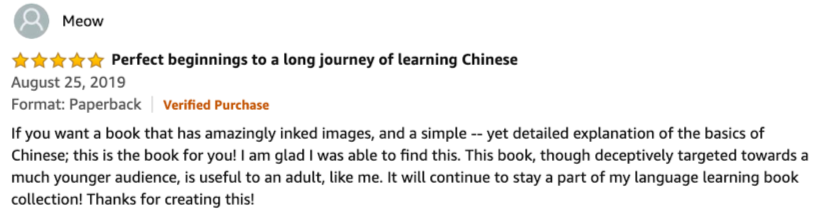

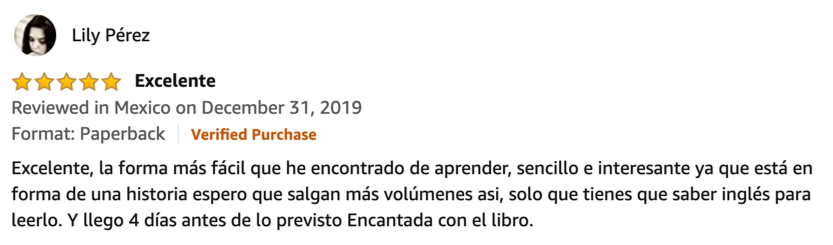

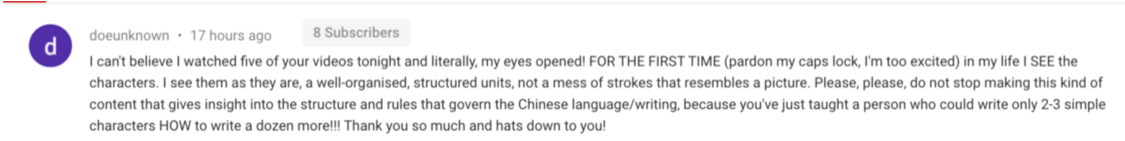

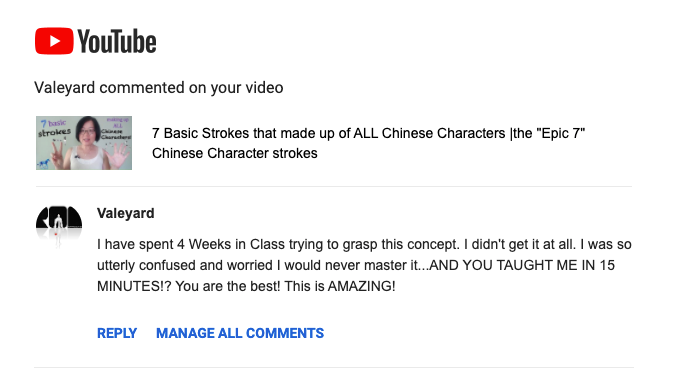

Her innovative approach has earned recognition from global design juries, major learning platforms, educators, parents, and learners alike.

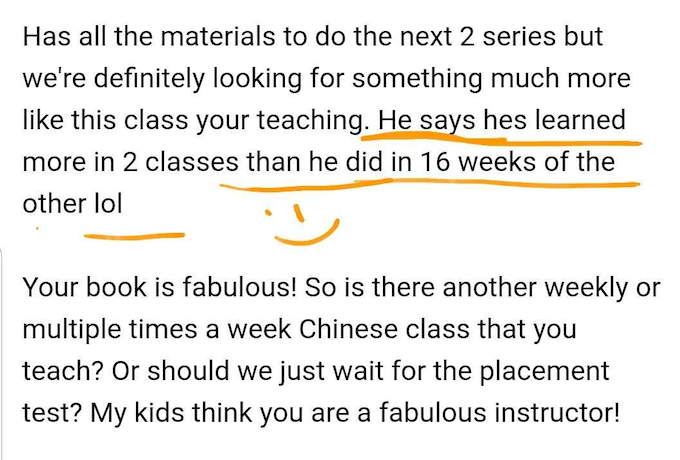

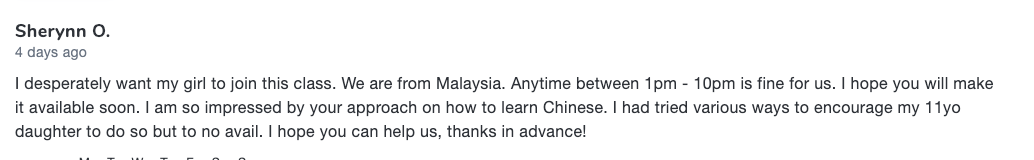

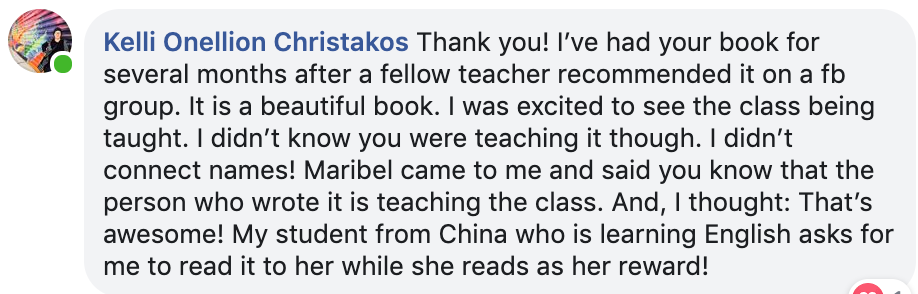

Explore the community voices below to see how Chinestory is making a difference in classrooms, homes, and hearts...and yes, a kid who begged me for more homework — scroll to the end to see that one.

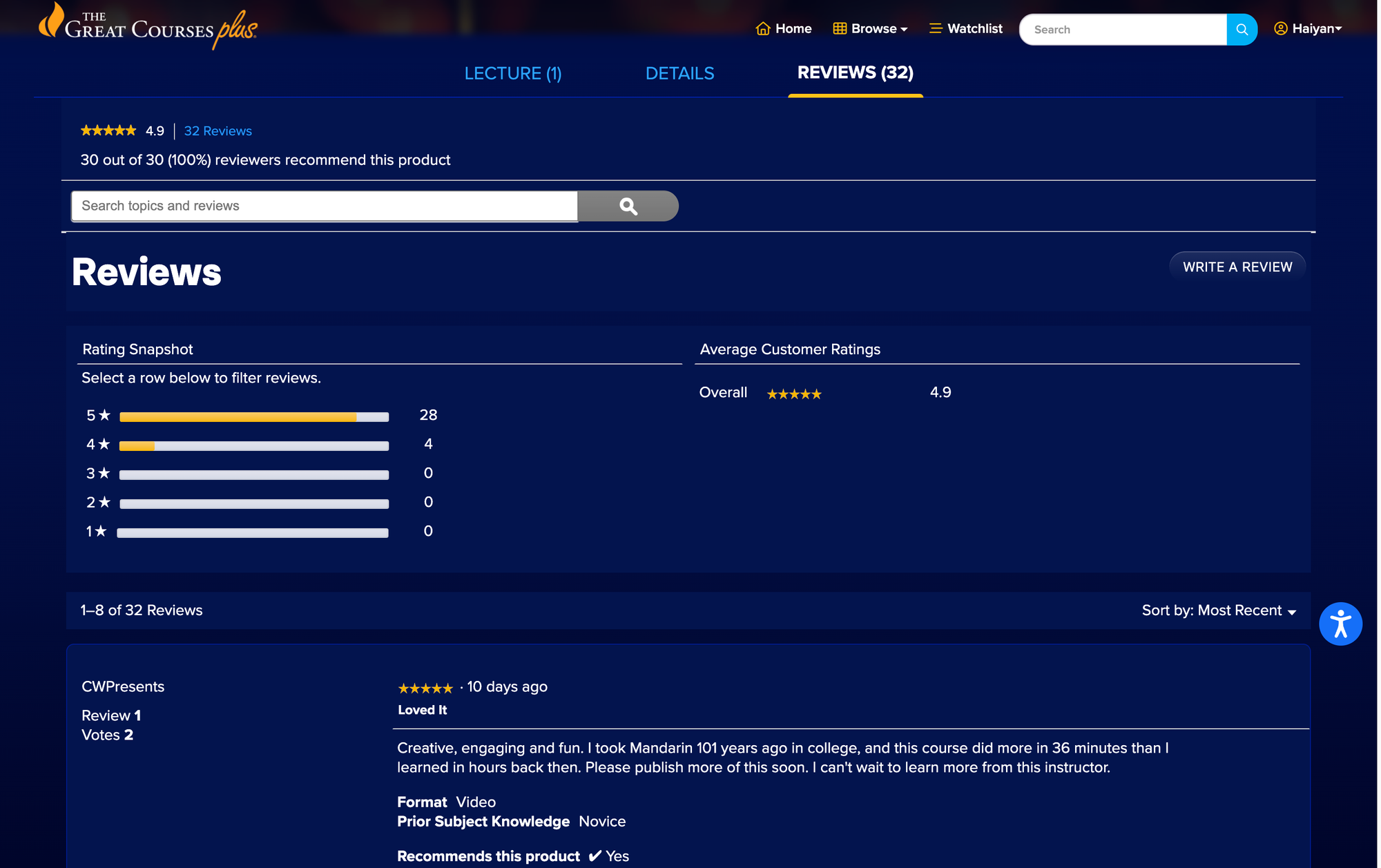

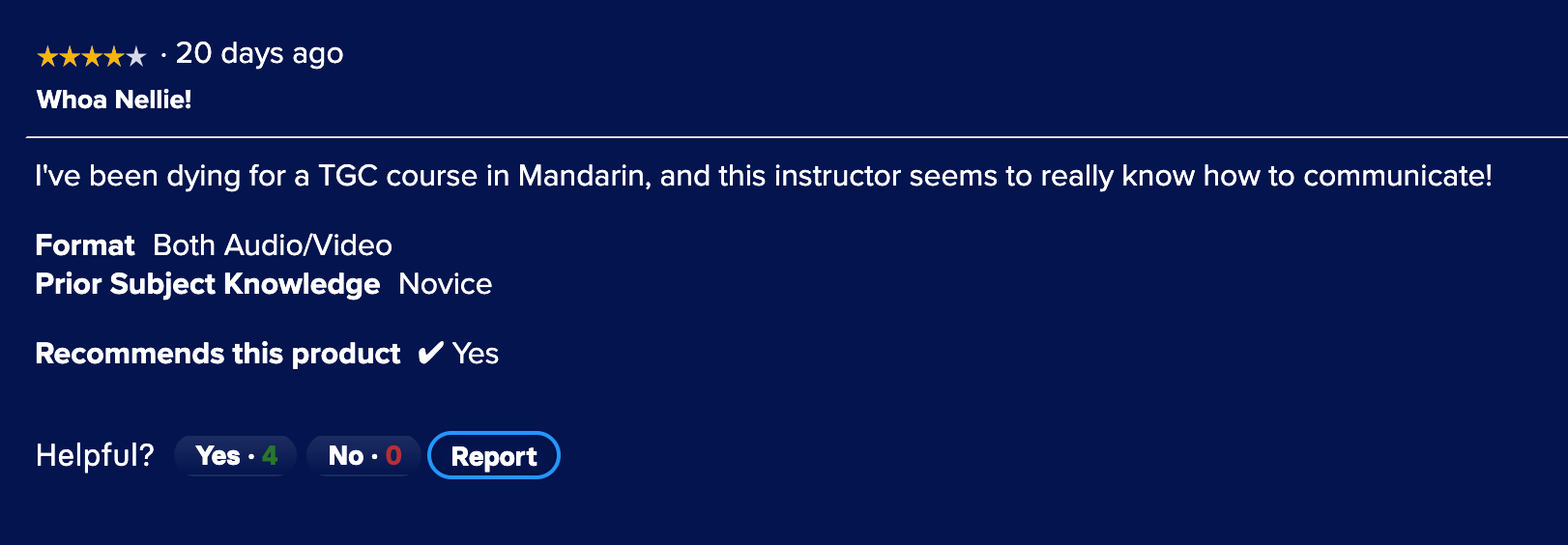

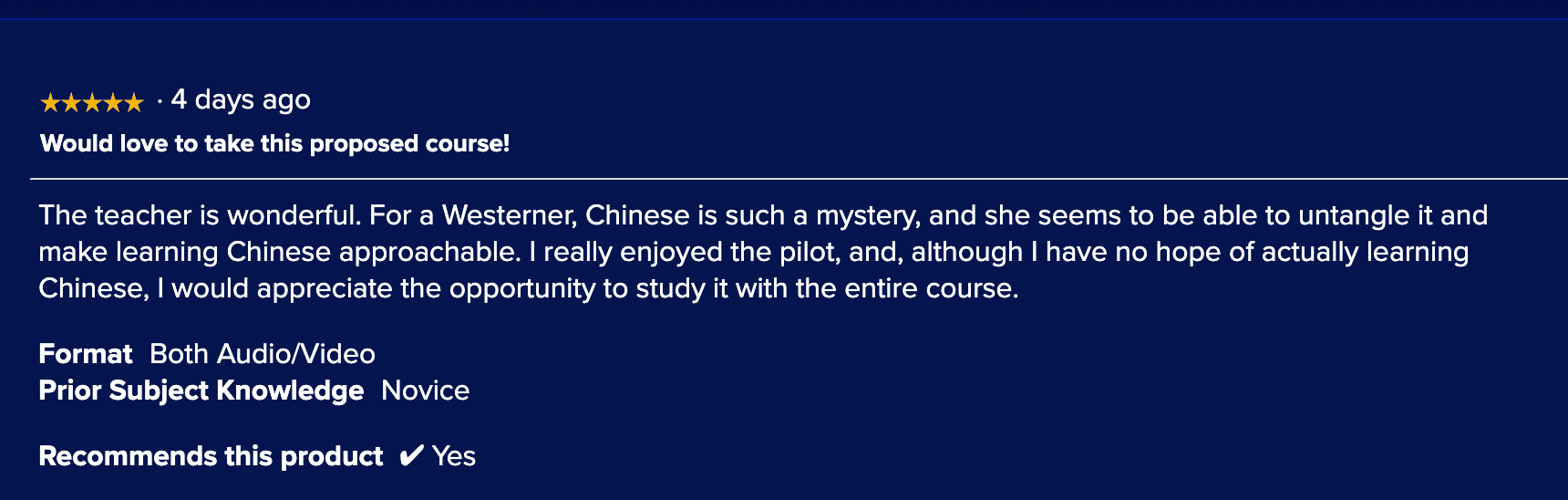

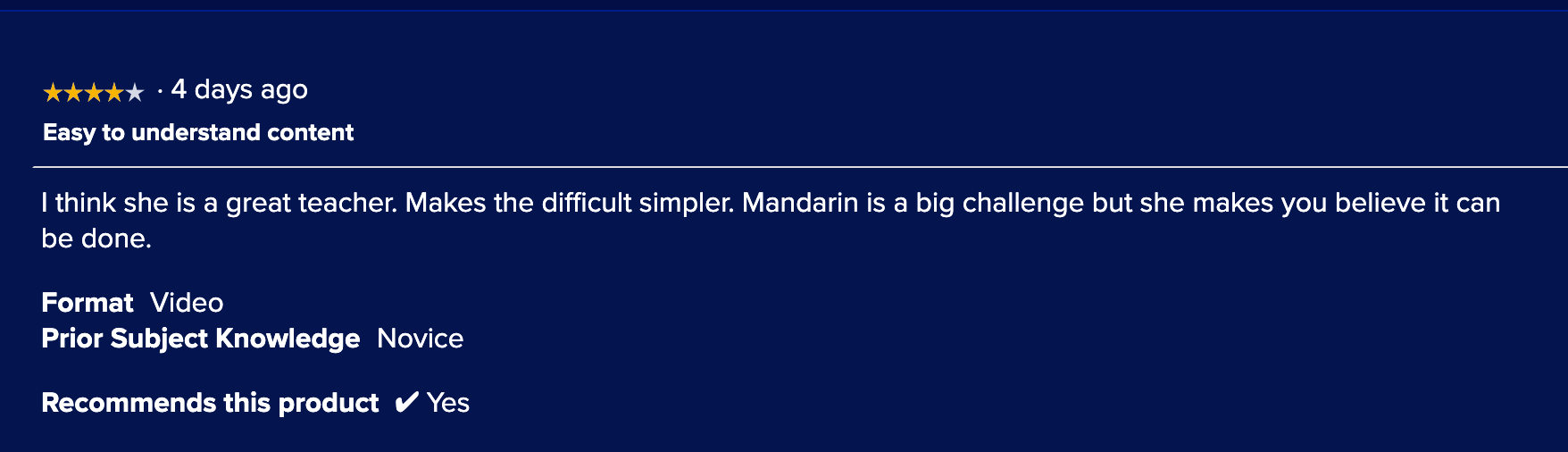

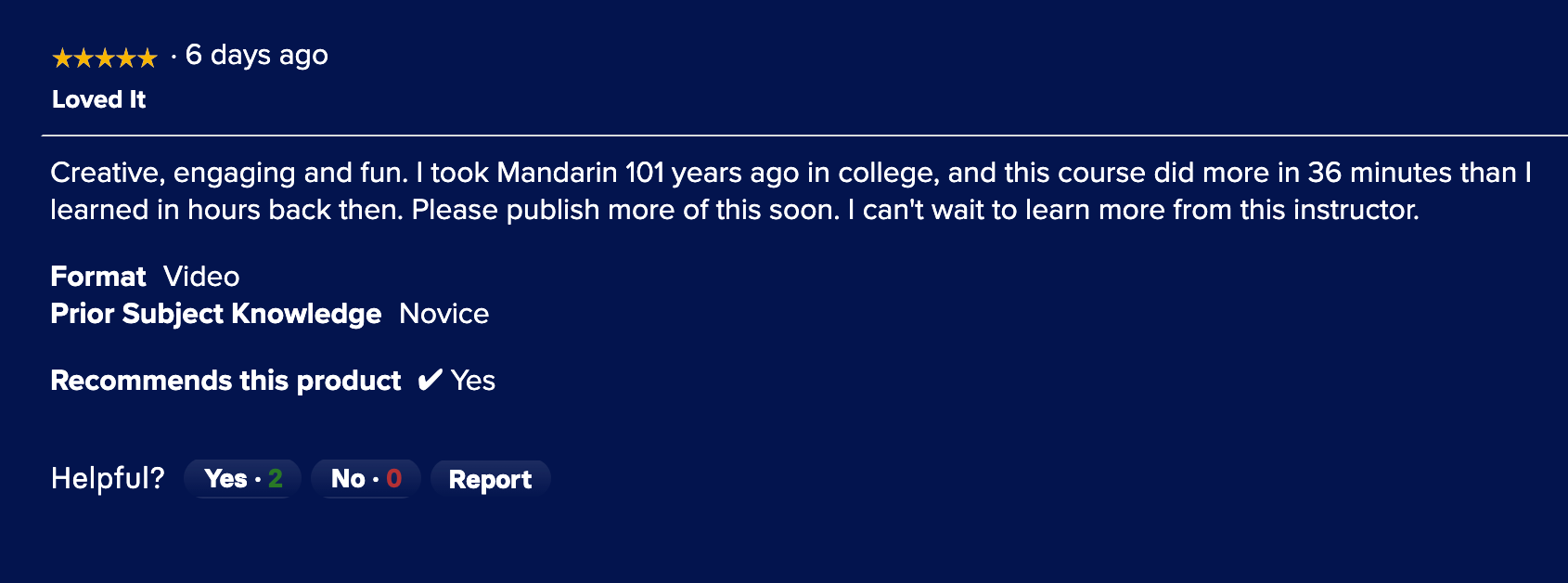

Screen shot of Dr. Fan's pilot episode of Mandarin Chinese class on Great Courses streaming platform

May the Horse be with you! 🐎✨